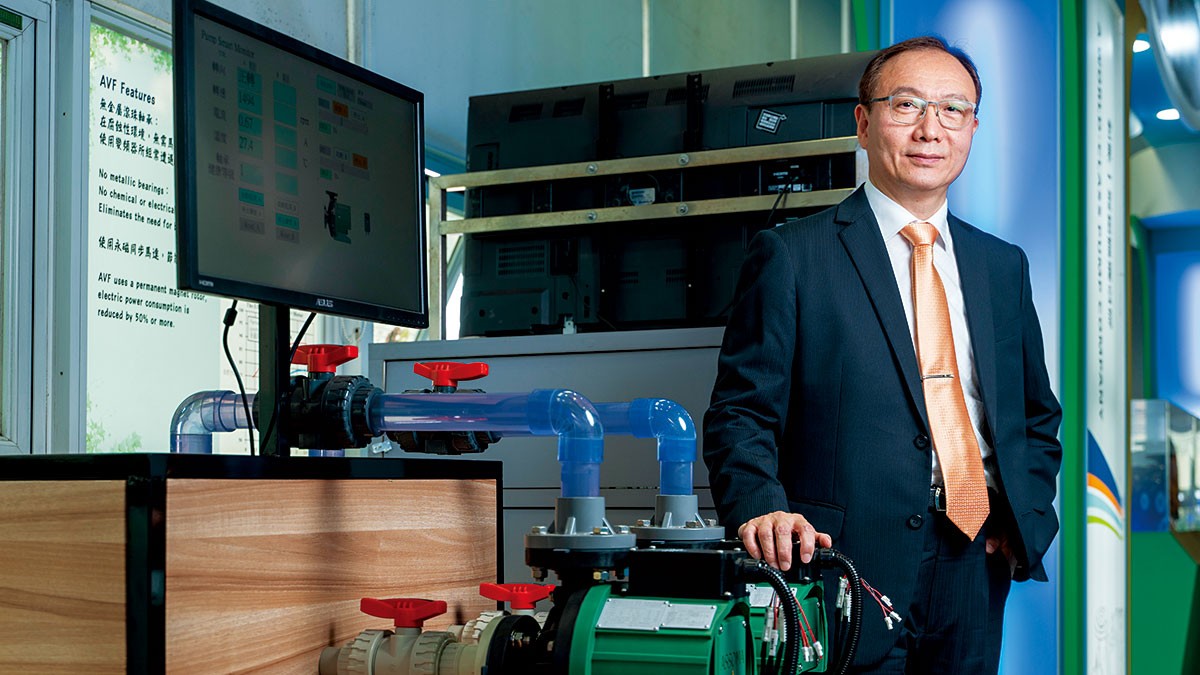

Speaking of ASSOMA INC., most people may feel unfamiliar, but their main product, pumps, is often indispensable in the manufacturing process of products we need daily. For instance, they are used in the cleaning equipment of soy sauce manufacturers, cooling systems for servers in the electronics, pharmaceutical, and technology industries, and even in the shipbuilding industry. The pump brand “ASSOMA” produced by ASSOMA INC. is widely used.

In 2004, during his EMBA studies, Zhixian Shi had the opportunity to learn about the Activity-Based Costing (ABC) system. He was deeply impressed by the potential benefits of this management system and discussed the possibility of implementation with the company’s finance and accounting manager. However, they ultimately decided not to proceed, as collecting the necessary data during the implementation process would be too labor-intensive.

In 2006, the company faced issues with production and sales coordination, leading to disrupted logistics and unreliable delivery schedules for parts and finished products, resulting in either shortages or excess inventory, which caused management challenges. To address these issues, ASSOMA INC. began implementing a management system to eliminate waste, shorten lead times, and improve product quality.

Before ASSOMA INC., several companies in the country had already implemented systems, such as the channel service provider Pro-Luck Co., Ltd. Therefore, ASSOMA initially used the clock-in system app adopted by Pro-Luck as a model.

Zhixian Shi mentioned that they first conducted a system inventory and rented the necessary software tools, such as the clock-in system app, which includes both mobile and desktop versions to meet the needs of internal and external staff. As for the implementation targets, ASSOMA chose to start with core business areas, including product project management systems and sales systems, introducing them as projects.

However, implementing the new system only in core business areas still faced some issues, such as app instability, the need for further customization, and the design of clock-in options.

These problems could be resolved through meetings with the system developer, customization, and redesigning the clock-in options. However, internal issues, such as low willingness to cooperate during clock-in and high error rates among less cooperative staff, also needed to be addressed. Additionally, some employees initially did not know how to fill in the data, with some writing “customer site service” in the clock-in content without clearly describing the actual operation. At this point, communication with the staff was necessary.

“Data like this, even if collected, lacks substantial meaning,” explained Hongyi Wu. At this time, it was necessary for supervisors to enhance communication with the staff. For example, supervisors could ask employees about the substantial content they wanted to express, help them fill in meaningful descriptions, provide templates for reference if needed, or even have supervisors teach employees one-on-one to fill in content with substantial meaning. Additionally, to ensure supervisors could implement communication and daily reporting, ASSOMA INC. included clock-in rate and accuracy as management indicators.

After implementation on the business side, ASSOMA’s employees planned to fill in data weekly and monthly. By analyzing the data returned by the business side, supervisors could quickly understand which activities within the eight-hour workday were necessary and valuable, and which were not. They could provide suggestions and adjust the content in advance, rather than only receiving after-the-fact reports from a few employees who planned their work in advance, leading to post hoc adjustments for various operations.